By Karen Burrows, managing director, Madeira UK

My immersion into the world of embroidery started in the eighties – before many of those reading this article were even born! We didn’t have mobile phones or computers – emails and social media were not even a consideration – yet looking back, industrial embroidery was actually advanced for its time.

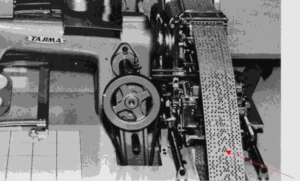

Initially evolving from lockstitch sewing machines, industrial embroidery machines began as single needle, multi-head, automated flat beds in the 1950s, moving to the 1990s where multi-functional multi-head machines with options for Cornely, chenille, sequins and boring were revolutionising the market.

Textile factories were still thriving, and I drove around most of the UK visiting companies producing and embroidering items as diverse as shoes, slippers, socks, hats, dresses, blouses, knitwear, sportswear, bedding and towels. I remember hearing orders for ‘two thousand dozen left panels’, or ‘five thousand dozen pockets’ and often cut pieces of garments such as sleeves or jacket fronts would be sent up and down the country to be embroidered then sent back to the manufacturer for making up.

Adapt to accommodate

The embroidery process itself was, dare I say, slightly easier, as it was mostly done prior to the product being stitched together, hence the flat beds and simple hoops worked fine. UK embroidery today is mostly onto finished goods, so the variety of hooping styles and options have had to adapt to accommodate intricacies such as embroidering a complete cap or a padded waterproof jacket.

While embroidery may have been more straightforward, the design creation and application were quite longwinded. The terminology ‘digitising’ was unknown. Originally it was ‘punching’, a term still referred to by some embroiderers. The desired design was created manually by literally ‘punching’ holes, initially by hand and later by machine, onto continuous paper tapes known as jacquards.

Jacquard: Named after Joseph M. Jacquard, inventor of the Jacquard Loom, which used a ‘punched’ card to weave a pattern.

These tapes were superseded in the late eighties by floppy discs, all having to be posted out, or if urgent, someone had to physically collect the design. The discs were double density 720kb, holding around 20 designs. Later, 1.44mb became the norm, taking approximately 40+ designs – some still used today!

Take for granted

Software development aided the transition as true ‘digitising’ became really sophisticated, when you could connect and download the design via a modem, which could take hours to download if the connection wasn’t strong! Today we take for granted the speed and efficiencies in creating and downloading designs using our modern technology and many machines have wireless connections, allowing almost instantaneous data transfer.

Threads

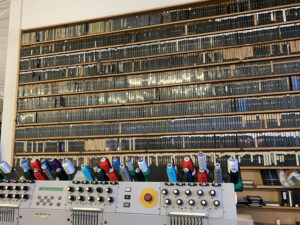

Clearly, machines need thread to produce the embroidery. Madeira has been manufacturing threads for more than 100 years. Like all thread producers, it began with cotton since this was before the introduction of polyester. Commercial requirements for decorative stitch and embroidery thread grew along with the speed of industrial embroidery machines. Progression towards more colour choice options via 8 to 16 needles and huge machines with 54 heads and more are available now.

The innovative Coloreel system launched recently, reverts to the use of a single needle but dyes and colours one single thread, supplied by Madeira, to create a coloured design without thread changes.

Inspiration and the desire for further development resulted in Madeira’s introduction of viscose embroidery thread ‘Madeira 40’ in the 1970s, now known as CLASSIC 40, closely followed by polyester ‘Neon’, now Polyneon, both later evolving to include a selection of thicknesses, plus a wide range of metallic and wool threads. Along the way, Madeira developed flame retardant and fire-resistant threads, threads with a ceramic core, which gives a perfect true velvet matt effect, and high conductive thread for specialist applications. Designers, fabrics, and technology lead the demand for more unusual creations and the highly skilled workforce, often with years of sewing machine experience used all thread varieties, often mixing weights and textures in one design, something we are seeing more of again.

Machine speeds have increased, laundering, dyestuffs and processes change, and chemical restrictions become more critical yet Madeira’s investment in the latest technology and machinery ensures the threads always perform to the highest level.

Sustainability

Today, sustainability is high on everyone’s radar. For Madeira it’s always been in our consciousness, since our HQ and factory is in Freiburg, Germany, a naturally green location due to the strict ecological and environmental codes in the Black Forest area. Madeira’s innate sense and actions towards sustainability ensure required standards are exceeded. The recent introduction of SENSA Green and POLYNEON Green offer even more sustainable options. Recognition of Madeira’s commitment came at the recent PCIAW dinner, when the company achieved the highest-level Sustainability Award.

I’ve been part of the industry embroidery community for a huge part of my life. I was there when Madeira UK exhibited at the first ever Printwear & Promotion show to include embroidery in the 1990s and at every single one since.

We have seen garment and textile production virtually disappear from the UK, been through the recession from 2008 to 2013 and now the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdowns. Some embroiderers continued their business to meet demand for NHS and other key worker uniforms, masks, and other PPE items and hence Madeira remained open to support the critical supply chain.

While embroidery is critical for the above, for branding, for fashion, for corporate identity and so much more, industrial embroidery is maybe not understood by the general public. Even though I’ve been part of the industrial embroidery industry for many years, my Mum though still thinks I go to work and sit on a rocking chair doing hand embroidery. When I told her I’d been to a spinning class she thought I was actually making thread!

Industrial embroidery is fascinating and enterprising, and I’m delighted it continues to thrive and develop.

I would like to thank Dominic Bunce of David Sharp Designs and Andy Anderson at Abstitch for sharing their memories also.

Printwear & Promotion The Total Promotional Package

Printwear & Promotion The Total Promotional Package